This story “auditioned” for me but was cut for a much abbreviated version.

Note: when referring to our “boatyard,” I mean the place where we stored and worked on our boat when it wasn’t in the water. Our boatyard was nowhere near the coast and was, in fact, a defunct chicken farm with long, narrow, empty buildings. A calf shed, also empty, where we stored and used all of our power tools, was also part of what we called our “shop.” I built a bathroom because there was none around. It consisted of a hole in the ground over which I positioned an old cane chair with the cane removed. Four six-foot, two by fours pounded into the ground served as the structure to which I stapled a tarp, to create three walls. The fourth “wall” faced the woods, so it didn’t need a door. A roll of toilet paper and done!

In the winter of 1987, we couldn’t work on the boat. It was on jack stands, outside; the snow was high and the temperatures low. So, our preparation for the trip, scheduled to begin in the spring of 1987, was actually a lot of time spent planning.

Especially Friday nights, when Dorin and I went out for drinks, it was all about the trip. Dorin made lists on napkins of additional equipment we had yet to acquire. Would it never end? I wondered. When I didn’t understand what something was, he’d draw a picture and give me instructions on how it would work: a sea anchor, a wind vane, an autopilot, safety harnesses, possibly a radar. It was fun and exciting, though I noted most of these items were about safety. And survival—much beyond anything we’d ever needed in the past while sailing the coast of Maine, and we’d been in a few dicey situations. Dorin had done a ton of reading on offshore sailing, so I knew he knew what he was talking about. It didn’t make me nervous though. Much.

We planned to leave in early May. To make the departure smoother, we decided I would give up my apartment at the end of March so I could store everything in the building at the boatyard, and Cor and I would move into Dorin’s one-bedroom apartment. That meant the couch for Cory.

It started to rain hard on March 28, a deluge really. The pickup truck I was using to move our furniture was open, but we didn’t have any choice, and we did have extra tarps. Cory’s teenage friends came to help, and we filled the pickup multiple times, making the half-hour trip to the boatyard, the windshield wipers furiously trying to give us at least a partial view of the road. We unloaded in the rain and went back for another load. And repeat. It was still raining on the second day; the ground around the building was getting waterlogged and deep ruts developed in the grassy area near the door of the calf shed where we were storing our stuff on the second floor. On the third and final day, the truck got stuck several times, and the guys, standing ankle deep in mud, had to push it out.

To get to the boatyard from where I lived in Waterville, we used either the bridge between Waterville and Winslow or the bridge between Fairfield and Benton. We noticed, with each crossing, that the Kennebec River was rapidly rising. We expected this each spring, but it usually caused only minor flooding in low areas. By the 30th of May, there were serious flood warnings on the radio and in the newspaper, and we were glad we were making our last trips across the Waterville bridge. The river was higher than we had ever seen it.

My son Bill called to say he was headed over to his grandmother-in law’s house because it might be in danger of washing away, as were other houses along her street in Winslow. She lived on the banks of the Kennebec on very low land. Each year the basements in these houses flooded, but usually it was not much more serious than that. He said he was going to help her move all her stuff to the second floor. Efforts had been made to move the books in the Winslow Library on that street to an upper floor. Parishioners from the Congregational church were also moving out anything that could be damaged.

Later that night, Bill called again to say the bridges might close. On April 1st, we decided to drive around and see what damage had been done. We went to the Waterville/Winslow bridge first. A policeman was allowing cars to cross, one at a time. We were astonished to see the water was almost to the bottom of the bridge. It was scary when we crossed, and the policeman closed it down immediately afterward.

Hours later, Bill called to say his grandmother-in-law’s house had broken loose from its foundation and floated down the river. Other houses followed. We drove further up the river to Fairfield where two bridges span the river and watched as a house came floating down the river, bumped into the larger bridge and then slowly bobbed and banged under, finally popping out on the other side and then rushing down the river toward Waterville. The next day we drove to Winslow where the Sebasticook and Kennebec Rivers merge, to find the city mostly under water. From our vantage point on a hill, we could see the water lapping at the eaves of the IGA Supermarket. A trip to Fairfield was the most shocking. The road that led onto the bridges from Fairfield and Benton, as well as the road connecting the two bridges, was completely gone.

But as the waters finally receded, we had to turn our attention to the boatyard. We could not waste another minute. Since Bill had taken over the business we owned together, I was able to work on the boat seven days a week, 12 hours a day. Cory’s school had given permission for him to leave school at the end of April because that’s when I told them we were leaving. He was squared away in terms of taking finals, so he came with me every day to work on the boat. He was easily as capable as any skilled adult. Dorin was still working at his practice during the week, so he joined us weekends to work on the boat. Seeing how far behind we were in preparations, two weeks later, Dorin stopped working and joined us every day. There were no days off.

Dorin had subscribed to a bulletin called SSCA (Seven Seas Cruising Association) and a pile of them had accumulated on the coffee table in his apartment. So, each night, when we arrived home from the boatyard, we read stories to each other of disasters that have befallen other cruising boaters on land and sea around the world.

This was Cory’s and my introduction to the subject of modern-day pirates. At first the concept seemed silly—except in movies, pirates were from the old, very old days. But, it seemed piracy was alive and well. We read that boats were boarded at gunpoint and robbed. Sometimes the passengers were set adrift in a lifeboat while the pirates sailed or motored their boat away. We discussed for hours the measures we would take to decrease the jeopardy, including several discussions about whether or not to take a gun, especially since Dorin owned a few. His opinion, voiced by many cruising people, was not to take a firearm. Those with firearms on board seemed to face a much higher mortality rate. I wasn’t so sure about this, but he was adamant, and the issue was resolved. No gun.

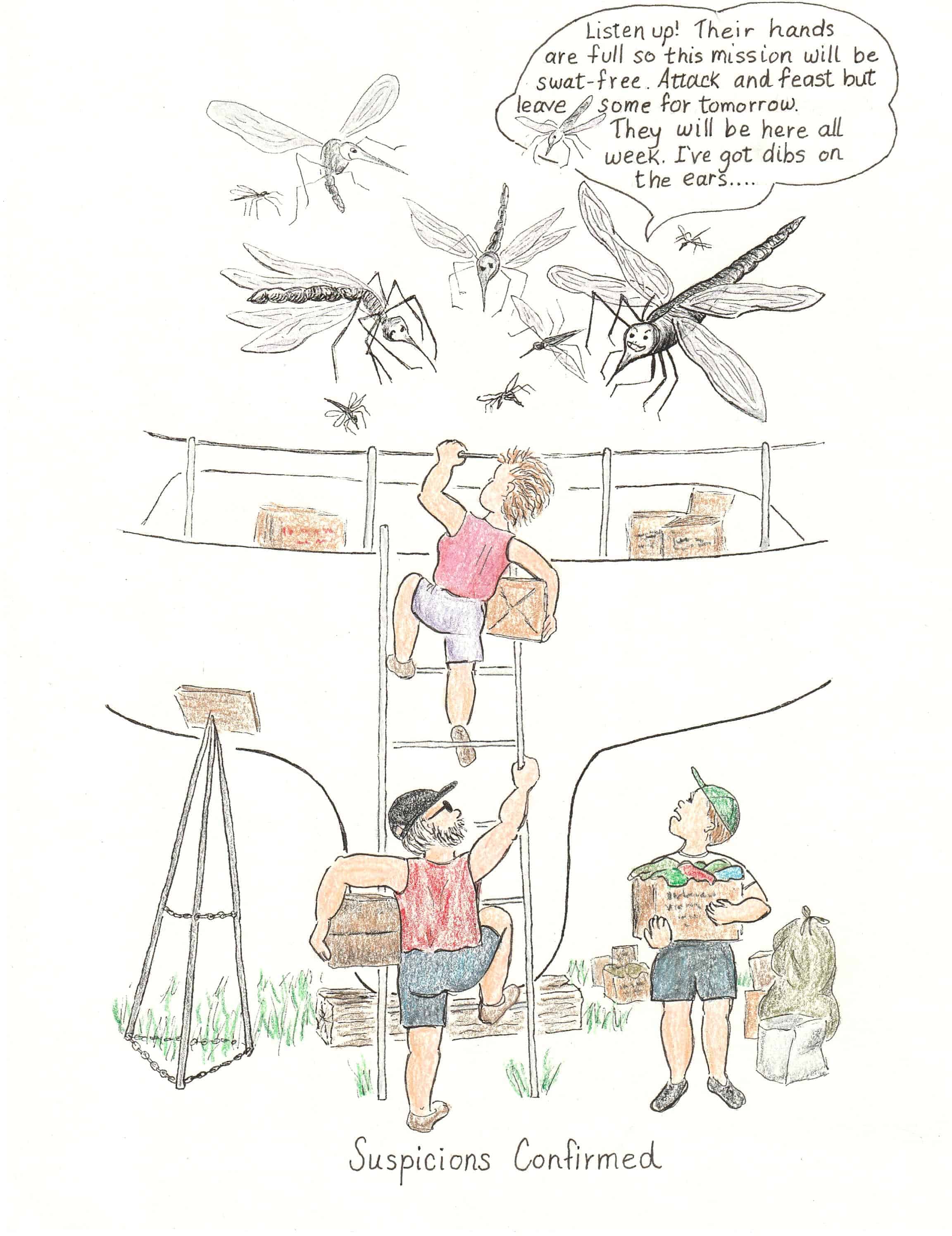

A neighbor at the boatyard planted a garden nearby, and we were not surprised that we were still there when the corn began pushing up through the soil. As we crossed each item off the list, it seemed we added two more. Cory notice that he and I crossed off more than Dorin. It was because, he explained to me, our items were small: caulk the windows, varnish the bulkhead. Dorin’s were of a larger scope: install the motor, install the secondary water system, revamp the electricity, replace the two-inch toe rails with five-inch mahogany—a challenge that I thought was out of the realm of possibility. The long, thick four-inch wide mahogany planks were not only tapered from bottom to top, but Dorin had cut slots to act as scuppers to allow sea water to run off the deck. These planks had to be bolted to the boat following the curve of the deck. Two friends came to help. It was very tense and took so much muscle power to coax, slowly, oh so slowly, the huge, massively strong mahogany planks to bend and conform. By the end of the day, we triumphed: we had one toe rail done—and now that we knew it could be done, we were able to do the other side with just the three of us. The neighbor’s corn was now calf high.

We reinforced the cabin sides with mahogany and changed the windows to opening ports, but much smaller, to minimize the danger of waves crashing through the ports or taking the cabin top clean off. We replaced the old exterior oak handrails with stronger ones. New, higher stanchions and lifelines were installed. Then I wove nylon twine into a diamond pattern from the top of the lifelines to the bottom so that we couldn’t slip through and off the boat. Dorin put a hasp on the mast so that ANYONE standing on the cabin top to lower the sails could attach the tether and not be swept off the boat. Having already swept Dorin off the deck, dangling him over the water as he clung to the boom, this one really appealed to me. The corn was knee high.

I called the boat movers three times because our estimates of when we would be ready were wrong. And wrong. And wrong again. The boat mover was not too happy with us as we kept changing the date and they kept juggling customers around. When we were finally ready to be hauled to the coast, though, it was not a problem. Self-respecting boaters already had their boats in the water….